skip to main |

skip to sidebar

A few days ago I wrote about the superb new Joe Harriott LP on Darrel Sheinman's Gearbox label. Actually, when I say new I should clarify that the music was recorded (quite beautifully recorded) in 1962. And when I say LP I should stipulate that it's perhaps more accurately described as an EP, with two tracks on each side and a concise playing time. ¶ It was this shorter playing time that enabled Darrel to put the music on 45rpm vinyl. More revolutions per minute are a good thing, opening the door to superior sound quality, and Gearbox isn't the first label to see the possibilities of combining high fidelity 45rpm twelve inch vinyl and great jazz. ¶ The renowned Blue Note catalogue is also releasing selected classic titles on 45. Because these albums were of course originally 33rpm releases, with concommitantly longer playing times, the Blue Notes have to be issued as double discs to accomodate their music.¶ My first thought when I heard about this project was why on earth I'd want to sacrifice the convenience of having all that great jazz on one disc. A lazy fellow like me doesn't want to rise from his comfortable modernist sofa and stroll across his space age pad to his turntable to change the record any more often than absolutely necessary. ¶ But my second thought was, I wonder what t

A few days ago I wrote about the superb new Joe Harriott LP on Darrel Sheinman's Gearbox label. Actually, when I say new I should clarify that the music was recorded (quite beautifully recorded) in 1962. And when I say LP I should stipulate that it's perhaps more accurately described as an EP, with two tracks on each side and a concise playing time. ¶ It was this shorter playing time that enabled Darrel to put the music on 45rpm vinyl. More revolutions per minute are a good thing, opening the door to superior sound quality, and Gearbox isn't the first label to see the possibilities of combining high fidelity 45rpm twelve inch vinyl and great jazz. ¶ The renowned Blue Note catalogue is also releasing selected classic titles on 45. Because these albums were of course originally 33rpm releases, with concommitantly longer playing times, the Blue Notes have to be issued as double discs to accomodate their music.¶ My first thought when I heard about this project was why on earth I'd want to sacrifice the convenience of having all that great jazz on one disc. A lazy fellow like me doesn't want to rise from his comfortable modernist sofa and stroll across his space age pad to his turntable to change the record any more often than absolutely necessary. ¶ But my second thought was, I wonder what t hose 45rpm transfers sound like; I bet they sound really good. And my third thought was holy shit, they've released Gil Melle's Patterns in Jazz. ¶ Now is not the time to expound on the irreplaceable and fascinating Gil Melle. Suffice to say that his smoothly avant garde, swinging West Coast jazz has earned my highest regard. So with the turntable set to 45 and being too lazy to change it back to 33, it was now an ideal time to compare the Gearbox Harriott and the Blue Note Melle. This is a particularly apt comparison because Darrel, the mastermind at Gearbox, is an admirer of the legendary label: "I collect original Blue Notes and have tried to recreate some of that feeling," he confides. And note that cool Harriott album cover, with its clean and elegant graphics evoking the classic Blue Note iconography. ¶ It's also an interesting comparison to make becase both albums are in magnificent mono, and both beautifully recorded, the Melle by the revered Rudy Van Gelder at his famed (and quirky) studio in his house in Hackensack, New Jersey. The

hose 45rpm transfers sound like; I bet they sound really good. And my third thought was holy shit, they've released Gil Melle's Patterns in Jazz. ¶ Now is not the time to expound on the irreplaceable and fascinating Gil Melle. Suffice to say that his smoothly avant garde, swinging West Coast jazz has earned my highest regard. So with the turntable set to 45 and being too lazy to change it back to 33, it was now an ideal time to compare the Gearbox Harriott and the Blue Note Melle. This is a particularly apt comparison because Darrel, the mastermind at Gearbox, is an admirer of the legendary label: "I collect original Blue Notes and have tried to recreate some of that feeling," he confides. And note that cool Harriott album cover, with its clean and elegant graphics evoking the classic Blue Note iconography. ¶ It's also an interesting comparison to make becase both albums are in magnificent mono, and both beautifully recorded, the Melle by the revered Rudy Van Gelder at his famed (and quirky) studio in his house in Hackensack, New Jersey. The  Harriott was recorded by some as yet unsung heroes of the BBC sound department in the Maida Vale studio, London. ¶ Musically both are outstanding pieces of work, and both sound great. To me the high frequencies on the Harriott sound a lot cleaner, a kind of 'silvery' sound whereas the Melle has a sort of a 'bronze' glow, if I may wax synaesthetic for a moment. There is something about the simplicity and purity of the Van Gelder recording. The timing is superb. Gil Melle's music has a hip sophisticated jollity and great richness to the baritone sax, which projects a kind of warm West Coast weirdness. The Melle possesses a mellow warmth and a sort of softer openness, as opposed to the sharply precise sense of space and air on the Harriott

Harriott was recorded by some as yet unsung heroes of the BBC sound department in the Maida Vale studio, London. ¶ Musically both are outstanding pieces of work, and both sound great. To me the high frequencies on the Harriott sound a lot cleaner, a kind of 'silvery' sound whereas the Melle has a sort of a 'bronze' glow, if I may wax synaesthetic for a moment. There is something about the simplicity and purity of the Van Gelder recording. The timing is superb. Gil Melle's music has a hip sophisticated jollity and great richness to the baritone sax, which projects a kind of warm West Coast weirdness. The Melle possesses a mellow warmth and a sort of softer openness, as opposed to the sharply precise sense of space and air on the Harriott.

¶ However, in terms of the vinyl quality there is no competition. The Blue Note Melle, on my copy, has some low level ticking noise. Faint, very infrequent, but it's there. Whereas the Gearbox Harriott seems almost bottomlessly clear and clean. ¶ The musicians on the Melle are Eddie Bert on trombone, Joe Cinderella on guitar (Melle employed interesting guitarists — Ta l Farlow, Joe Mecca and Cinderella), Oscar Pettiford on bass, Ed Thigpen on drums and Gil Melle on baritone sax. The 45rpm reissue was remastered by Kevin Gray and Steve Hoffman at AcousTech

l Farlow, Joe Mecca and Cinderella), Oscar Pettiford on bass, Ed Thigpen on drums and Gil Melle on baritone sax. The 45rpm reissue was remastered by Kevin Gray and Steve Hoffman at AcousTech.

The personnel on the Harriott are Shake Keane, flugelhorn and trumpet, Pat Smythe on piano, Coleridge Goode on bass, Bobby Orr on drums and Joe Harriott alto saxophone. It was remastered on valve equipment by Jeremy Cooper at Soundtrap.

It all began two days ago. Thanks to a certain record store in Chicago for which I have a sneaking regard, I was alerted to the presence of a new Joe Harriott album.¶ Joe Harriott is a lost great of British jazz, someone who slipped through the cracks. He was also, some might say, the West Indian riposte to Charlie Parker. My friend Michael Garrick, a great exponent of Harriott, and himself a living jazz legend, describes him as "a superb altoist and ground breaking thinker in British jazz". ¶ Harvey Pekar describes Harriott and his partner in time, trumpeter Shake Keane (you've got to love that name) as "among the finest avant garde artists in the early 60s." Well, they may be avant garde but I have to add that they can boogie. ¶ I mostly know Joe Harriott's work through his two remarkab

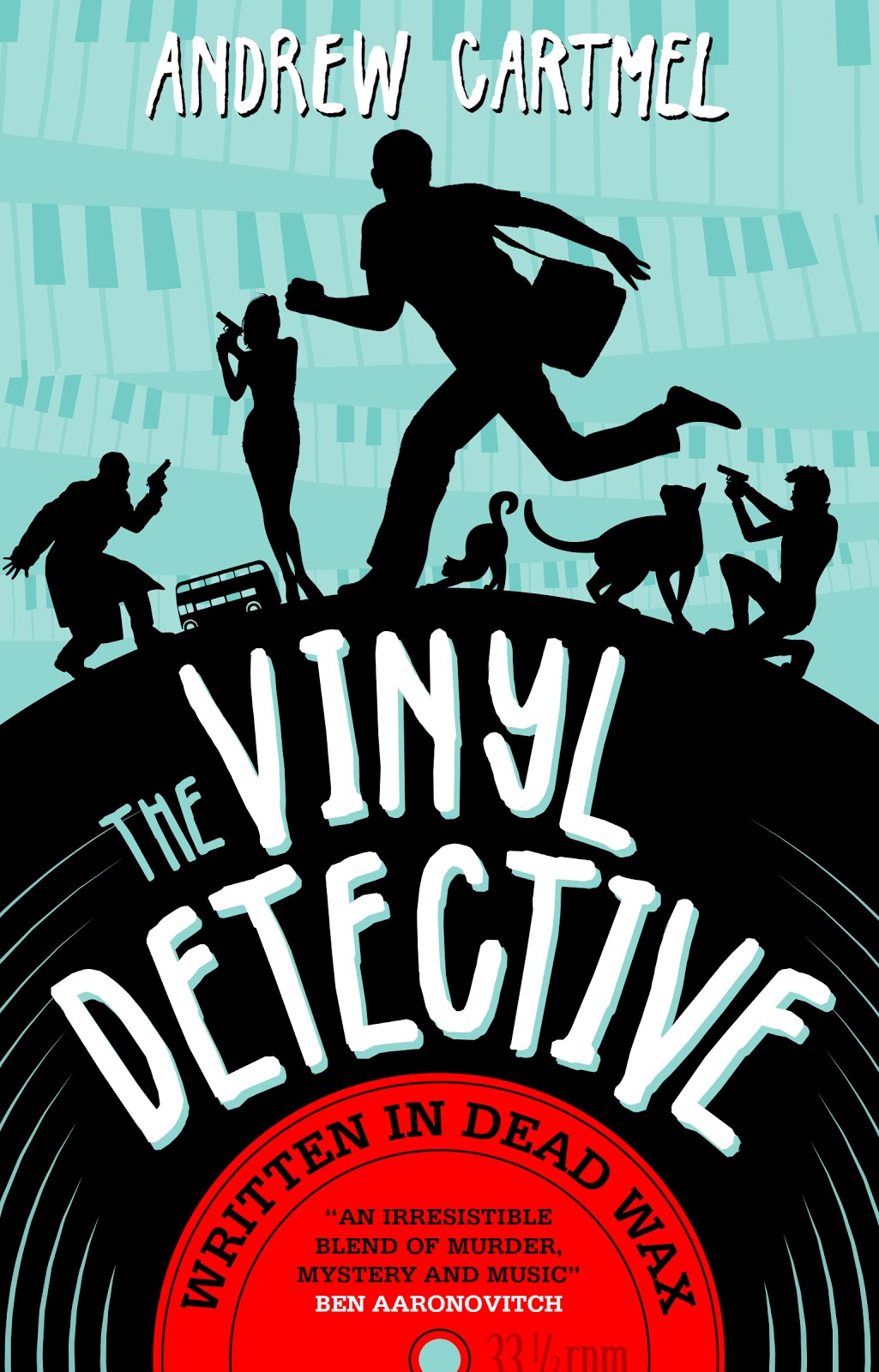

It all began two days ago. Thanks to a certain record store in Chicago for which I have a sneaking regard, I was alerted to the presence of a new Joe Harriott album.¶ Joe Harriott is a lost great of British jazz, someone who slipped through the cracks. He was also, some might say, the West Indian riposte to Charlie Parker. My friend Michael Garrick, a great exponent of Harriott, and himself a living jazz legend, describes him as "a superb altoist and ground breaking thinker in British jazz". ¶ Harvey Pekar describes Harriott and his partner in time, trumpeter Shake Keane (you've got to love that name) as "among the finest avant garde artists in the early 60s." Well, they may be avant garde but I have to add that they can boogie. ¶ I mostly know Joe Harriott's work through his two remarkab le Indo Jazz Fusion albums (it was a red letter day at the Cartmel pad when I finally got my hands on those beauties, I can tell you) and Mike Garrick's equally remarkable album of big band versions of Harriott's music. A new Harriott record was great news. ¶ This is a previously lost performance from 1962, resurrected on high end vinyl in a limited edition. Normally when I hear the words limited edition I reach for my revolver (and I don't mean turntable), but this was an intriguing proposition. ¶ It is the first release from a new British label called Gearbox, the brainchild of Darrel Sheinman and avowedly dedicated to preserving memorable and well recorded music on high quality vinyl pressings. ¶ The Harriott performance was from a BBC session in the Maida Vale Studios recorded in the heyday of good sound by some chaps who knew what they were aboutl. ¶ The record is only 15 minutes long and not cheap. So I hesitated. Yes, I hesitated for about three tenths of a second, then I bought it. ¶ When I got home I put it on the turntable with considerable trepidation. Would I get burned again? The last time I shelled out for a premium piece of "limited edition" vinyl, it turned out to be a costly dog (sorry, Marco, but it's true). ¶ Because the Harriott record has such a brief playing time it made sense to record it at 45rpm. This is a good thing because the faster you feed the vinyl surface towards the questing insect proboscis of the gramophone needle, the more information you can present in a given time. In

le Indo Jazz Fusion albums (it was a red letter day at the Cartmel pad when I finally got my hands on those beauties, I can tell you) and Mike Garrick's equally remarkable album of big band versions of Harriott's music. A new Harriott record was great news. ¶ This is a previously lost performance from 1962, resurrected on high end vinyl in a limited edition. Normally when I hear the words limited edition I reach for my revolver (and I don't mean turntable), but this was an intriguing proposition. ¶ It is the first release from a new British label called Gearbox, the brainchild of Darrel Sheinman and avowedly dedicated to preserving memorable and well recorded music on high quality vinyl pressings. ¶ The Harriott performance was from a BBC session in the Maida Vale Studios recorded in the heyday of good sound by some chaps who knew what they were aboutl. ¶ The record is only 15 minutes long and not cheap. So I hesitated. Yes, I hesitated for about three tenths of a second, then I bought it. ¶ When I got home I put it on the turntable with considerable trepidation. Would I get burned again? The last time I shelled out for a premium piece of "limited edition" vinyl, it turned out to be a costly dog (sorry, Marco, but it's true). ¶ Because the Harriott record has such a brief playing time it made sense to record it at 45rpm. This is a good thing because the faster you feed the vinyl surface towards the questing insect proboscis of the gramophone needle, the more information you can present in a given time. In  other words, there's more scope for accurately reproducing the music.¶ When I sent Darrel Sheinman an email asking about the record he offered the following encouraging observation: "Side length was pretty evenly balanced for optimum groove spacing so as to keep the re-mastering levels equal on each side." When I heard that I began to think these guys knew what they were doing. ¶ Normally 45rpm records are singles and I've never listened to singles. (For one thing you need to keep getting up all the time to refresh the music.) So it is a rare day when I change my turntable from 33 to 45. I go through the elaborate and immensely demanding procedure (basically you just throw a switch) and, fingers crossed and breath bated, I put the record on. ¶ Utter silence. That's what ensued when I dropped the needle into the run in groove. I almost checked to see if I'd missed the disc altogether. This is tremendous cause for rejoicing. In a sense, the best sound you can hear on a record is no sound at all. If the vinyl is so quiet at the start of a record it means it's a really high quality precision pressing and once the music starts that, too, is likely to utterly deliver the goods. And deliver the goods this did.¶ There is a beautiful transparency to the first cut, Shepherd's Serenade and an interesting room sound is evident. It's a real place with real music being played in it, captured with amazing precision. The openness of the sound and the glorious transparency are present throughout. It is, as they say, an open window on the music. The rhythmic accuracy of the recording mak

other words, there's more scope for accurately reproducing the music.¶ When I sent Darrel Sheinman an email asking about the record he offered the following encouraging observation: "Side length was pretty evenly balanced for optimum groove spacing so as to keep the re-mastering levels equal on each side." When I heard that I began to think these guys knew what they were doing. ¶ Normally 45rpm records are singles and I've never listened to singles. (For one thing you need to keep getting up all the time to refresh the music.) So it is a rare day when I change my turntable from 33 to 45. I go through the elaborate and immensely demanding procedure (basically you just throw a switch) and, fingers crossed and breath bated, I put the record on. ¶ Utter silence. That's what ensued when I dropped the needle into the run in groove. I almost checked to see if I'd missed the disc altogether. This is tremendous cause for rejoicing. In a sense, the best sound you can hear on a record is no sound at all. If the vinyl is so quiet at the start of a record it means it's a really high quality precision pressing and once the music starts that, too, is likely to utterly deliver the goods. And deliver the goods this did.¶ There is a beautiful transparency to the first cut, Shepherd's Serenade and an interesting room sound is evident. It's a real place with real music being played in it, captured with amazing precision. The openness of the sound and the glorious transparency are present throughout. It is, as they say, an open window on the music. The rhythmic accuracy of the recording mak es Variations on Monk (written by Dizzy Reece) come briskly alive. And then we're into Harriott's joyous original Tonal (Mike Garrick does a classic big band version of this). The other side of the record also features one composition by Reece (the aforementioned Shepherd's Serenade) and one by Harriott (Pictures). And they're equally impressive. ¶ There's a cool perfection to the recording quality here which fits well with a certain austere sharpness in Joe Harriott's great music. I'm blown away. ¶ Darrel Sheinman at Gearbox and Jeremy Cooper at Soundtrap, who did the valve remastering (yes, valve re-mastering! Get thee behind me, transistors) are those rarest of specimens. Men who actually know what they're doing. They'

es Variations on Monk (written by Dizzy Reece) come briskly alive. And then we're into Harriott's joyous original Tonal (Mike Garrick does a classic big band version of this). The other side of the record also features one composition by Reece (the aforementioned Shepherd's Serenade) and one by Harriott (Pictures). And they're equally impressive. ¶ There's a cool perfection to the recording quality here which fits well with a certain austere sharpness in Joe Harriott's great music. I'm blown away. ¶ Darrel Sheinman at Gearbox and Jeremy Cooper at Soundtrap, who did the valve remastering (yes, valve re-mastering! Get thee behind me, transistors) are those rarest of specimens. Men who actually know what they're doing. They' ve taken a forgotten performance by a neglected jazz great and given it new life in stunning sound. And so getting up early to go to a record shop called Sister Ray in Soho on a rainy Thursday morning in November proved to be exactly the right thing to do. ¶ What do you know? For once being a jazz lover and a hi-fi nut has actually paid off.

ve taken a forgotten performance by a neglected jazz great and given it new life in stunning sound. And so getting up early to go to a record shop called Sister Ray in Soho on a rainy Thursday morning in November proved to be exactly the right thing to do. ¶ What do you know? For once being a jazz lover and a hi-fi nut has actually paid off.

A few days ago I wrote about the superb new Joe Harriott LP on Darrel Sheinman's Gearbox label. Actually, when I say new I should clarify that the music was recorded (quite beautifully recorded) in 1962. And when I say LP I should stipulate that it's perhaps more accurately described as an EP, with two tracks on each side and a concise playing time. ¶ It was this shorter playing time that enabled Darrel to put the music on 45rpm vinyl. More revolutions per minute are a good thing, opening the door to superior sound quality, and Gearbox isn't the first label to see the possibilities of combining high fidelity 45rpm twelve inch vinyl and great jazz. ¶ The renowned Blue Note catalogue is also releasing selected classic titles on 45. Because these albums were of course originally 33rpm releases, with concommitantly longer playing times, the Blue Notes have to be issued as double discs to accomodate their music.¶ My first thought when I heard about this project was why on earth I'd want to sacrifice the convenience of having all that great jazz on one disc. A lazy fellow like me doesn't want to rise from his comfortable modernist sofa and stroll across his space age pad to his turntable to change the record any more often than absolutely necessary. ¶ But my second thought was, I wonder what t

A few days ago I wrote about the superb new Joe Harriott LP on Darrel Sheinman's Gearbox label. Actually, when I say new I should clarify that the music was recorded (quite beautifully recorded) in 1962. And when I say LP I should stipulate that it's perhaps more accurately described as an EP, with two tracks on each side and a concise playing time. ¶ It was this shorter playing time that enabled Darrel to put the music on 45rpm vinyl. More revolutions per minute are a good thing, opening the door to superior sound quality, and Gearbox isn't the first label to see the possibilities of combining high fidelity 45rpm twelve inch vinyl and great jazz. ¶ The renowned Blue Note catalogue is also releasing selected classic titles on 45. Because these albums were of course originally 33rpm releases, with concommitantly longer playing times, the Blue Notes have to be issued as double discs to accomodate their music.¶ My first thought when I heard about this project was why on earth I'd want to sacrifice the convenience of having all that great jazz on one disc. A lazy fellow like me doesn't want to rise from his comfortable modernist sofa and stroll across his space age pad to his turntable to change the record any more often than absolutely necessary. ¶ But my second thought was, I wonder what t hose 45rpm transfers sound like; I bet they sound really good. And my third thought was holy shit, they've released Gil Melle's Patterns in Jazz. ¶ Now is not the time to expound on the irreplaceable and fascinating Gil Melle. Suffice to say that his smoothly avant garde, swinging West Coast jazz has earned my highest regard. So with the turntable set to 45 and being too lazy to change it back to 33, it was now an ideal time to compare the Gearbox Harriott and the Blue Note Melle. This is a particularly apt comparison because Darrel, the mastermind at Gearbox, is an admirer of the legendary label: "I collect original Blue Notes and have tried to recreate some of that feeling," he confides. And note that cool Harriott album cover, with its clean and elegant graphics evoking the classic Blue Note iconography. ¶ It's also an interesting comparison to make becase both albums are in magnificent mono, and both beautifully recorded, the Melle by the revered Rudy Van Gelder at his famed (and quirky) studio in his house in Hackensack, New Jersey. The

hose 45rpm transfers sound like; I bet they sound really good. And my third thought was holy shit, they've released Gil Melle's Patterns in Jazz. ¶ Now is not the time to expound on the irreplaceable and fascinating Gil Melle. Suffice to say that his smoothly avant garde, swinging West Coast jazz has earned my highest regard. So with the turntable set to 45 and being too lazy to change it back to 33, it was now an ideal time to compare the Gearbox Harriott and the Blue Note Melle. This is a particularly apt comparison because Darrel, the mastermind at Gearbox, is an admirer of the legendary label: "I collect original Blue Notes and have tried to recreate some of that feeling," he confides. And note that cool Harriott album cover, with its clean and elegant graphics evoking the classic Blue Note iconography. ¶ It's also an interesting comparison to make becase both albums are in magnificent mono, and both beautifully recorded, the Melle by the revered Rudy Van Gelder at his famed (and quirky) studio in his house in Hackensack, New Jersey. The  Harriott was recorded by some as yet unsung heroes of the BBC sound department in the Maida Vale studio, London. ¶ Musically both are outstanding pieces of work, and both sound great. To me the high frequencies on the Harriott sound a lot cleaner, a kind of 'silvery' sound whereas the Melle has a sort of a 'bronze' glow, if I may wax synaesthetic for a moment. There is something about the simplicity and purity of the Van Gelder recording. The timing is superb. Gil Melle's music has a hip sophisticated jollity and great richness to the baritone sax, which projects a kind of warm West Coast weirdness. The Melle possesses a mellow warmth and a sort of softer openness, as opposed to the sharply precise sense of space and air on the Harriott. ¶ However, in terms of the vinyl quality there is no competition. The Blue Note Melle, on my copy, has some low level ticking noise. Faint, very infrequent, but it's there. Whereas the Gearbox Harriott seems almost bottomlessly clear and clean. ¶ The musicians on the Melle are Eddie Bert on trombone, Joe Cinderella on guitar (Melle employed interesting guitarists — Ta

Harriott was recorded by some as yet unsung heroes of the BBC sound department in the Maida Vale studio, London. ¶ Musically both are outstanding pieces of work, and both sound great. To me the high frequencies on the Harriott sound a lot cleaner, a kind of 'silvery' sound whereas the Melle has a sort of a 'bronze' glow, if I may wax synaesthetic for a moment. There is something about the simplicity and purity of the Van Gelder recording. The timing is superb. Gil Melle's music has a hip sophisticated jollity and great richness to the baritone sax, which projects a kind of warm West Coast weirdness. The Melle possesses a mellow warmth and a sort of softer openness, as opposed to the sharply precise sense of space and air on the Harriott. ¶ However, in terms of the vinyl quality there is no competition. The Blue Note Melle, on my copy, has some low level ticking noise. Faint, very infrequent, but it's there. Whereas the Gearbox Harriott seems almost bottomlessly clear and clean. ¶ The musicians on the Melle are Eddie Bert on trombone, Joe Cinderella on guitar (Melle employed interesting guitarists — Ta l Farlow, Joe Mecca and Cinderella), Oscar Pettiford on bass, Ed Thigpen on drums and Gil Melle on baritone sax. The 45rpm reissue was remastered by Kevin Gray and Steve Hoffman at AcousTech. The personnel on the Harriott are Shake Keane, flugelhorn and trumpet, Pat Smythe on piano, Coleridge Goode on bass, Bobby Orr on drums and Joe Harriott alto saxophone. It was remastered on valve equipment by Jeremy Cooper at Soundtrap.

l Farlow, Joe Mecca and Cinderella), Oscar Pettiford on bass, Ed Thigpen on drums and Gil Melle on baritone sax. The 45rpm reissue was remastered by Kevin Gray and Steve Hoffman at AcousTech. The personnel on the Harriott are Shake Keane, flugelhorn and trumpet, Pat Smythe on piano, Coleridge Goode on bass, Bobby Orr on drums and Joe Harriott alto saxophone. It was remastered on valve equipment by Jeremy Cooper at Soundtrap.